You’ve probably heard that you need active reading strategies in order to understand and remember more.

The question is… what exactly are these strategies and how can you use them effectively?

On this page, we’re going to cover what I consider to be the best active reading techniques.

According to whom?

First, scientific research.

Second, I’ll share techniques I learned as part of my journey towards getting two MAs, a PhD and working for decades as a research and writer.

So if you like the best of both proven research and lived experience, you’re in the right spot to learn how to read better and faster.

Let’s get started.

Active reading is distinguished from passive reading, an activity where you read just to read.

By contrast, the active reading process involves strategies. These strategies may include:

The most important aspect is that you have a specific goal in mind. For example, as I teach in How to Memorize a Textbook , a goal might be to extract and remember three points per chapter.

Here’s another example:

Whereas passive reading might involve just picking up the latest book to hit the market, active reading involves researching books that belong to a specific example.

Some of my personal case studies have involved the Advaita Vedanta research project that led to my TEDxTalk, Two Easily Remembered Questions That Silence Negative Thoughts .

All of the books I read for this project are compiled in the bibliography of The Victorious Mind: How to Master Memory, Meditation and Mental Well-Being .

The success of these projects required reading actively in each of the following ways we’re about to cover in depth.

As you go through each of the following strategies, I suggest you take notes. Why?

Because it is one of the best possible techniques you can do to really switch on the power of fully engaged reading.

I take notes in a number of ways. These include:

I have written a lot about many unusual note taking techniques. Two of my favorite include using index cards in different ways.

The first way involves capturing individual ideas on individual cards. I usually decide on how many notes I will take from each chapter to keep things simple and follow the “less is more” principle.

Next, I will make the first card have the title and name of the book. Each card thereafter will feature a quote, key point or my own observations. I always add the page number in case I need to find my way back to the place in the book for context.

The second style involves cramming everything on to just 1-2 index cards per book.

For example, when going through certain books, like some novels I’ve read for a research project on consciousness, there’s no need for multiple index cards. So I use one index card as I read and jot down first the page number and then the quote or idea.

This single card keeps my attention focused on the goal of reading the book. Sure, some of them might be entertaining, but here’s what matters:

Using the index card while reading helps me remember the goal of paying attention to the theme of consciousness – the core reason I’m reading the book in the first place.

One thing that puzzles me about people who practice speed reading is their contradictions.

For example, they’ll tell you how to stop subvocalizing , yet at the same time instruct that you should ask questions while reading.

How exactly is this possible? I’m not sure, but I can tell you that I ask questions all the time and vocalize on purpose.

In fact, to make reading extra-active, you can adopt the voice of particular people in your mind. For example, you can pretend that you are Einstein and ask questions in a German accent.

Now that’s what I call active and engaging. And the best part is how it all helps with retaining new information for the long term.

What questions should you ask? The obvious ones, of course:

But you will make your reading even more active by asking other questions.

A first level of additional activity would be to add “else” to each question above:

If you can push for 5 answers in each case, your engagement will go through the roof.

I would suggest you also ask questions like:

There are potentially hundreds of questions. The more you practice asking both simple and more complex questions, the more powerful questions will come to mind.

A lot of people tell you to visualize while reading.

That’s great advice, but what if you have aphantasia (lack of a mind’s eye)?

The answer, whether you have this condition or not, is to widen your options.

In the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass , you’ll learn to visualize using multiple senses that we remember through the KAVE COGS formula:

Touching on each of these “Magnetic Modes” brings even the most abstract information to life, especially if you’re using mnemonic devices .

Here are some examples of active reading using a few such devices:

There’s no doubt that many people will struggle with some of these active reading activities in the beginning. We often haven’t used any of them since early childhood, and even then, they were neither strategic or as sophisticated as they could have been.

The trick is to just get started. Study more accelerated learning techniques like these as you go. Practice more often and regularly analyze your results.

Amongst the many bad pieces of advice given in the speed reading community, reading without stopping is amongst the worst.

In reality, the path to reading faster is to increase your vocabulary. That way, you won’t be slowed down in the future. You’ll just know what more words mean.

Here’s a simple routine you can follow when you don’t recognize a word while reading:

I suggest that you do not stop to look words up as you go, at least not in an online dictionary.

Doing so interrupts the routine I just shared and also opens you to all kinds of distractions. It’s perfectly fine to save the material for later and doing so improves your memory while fending off digital amnesia .

Sadly, I used to skip charts and graphs. This bad reading habit slowed my path to understanding and weakened my visual interpretation abilities.

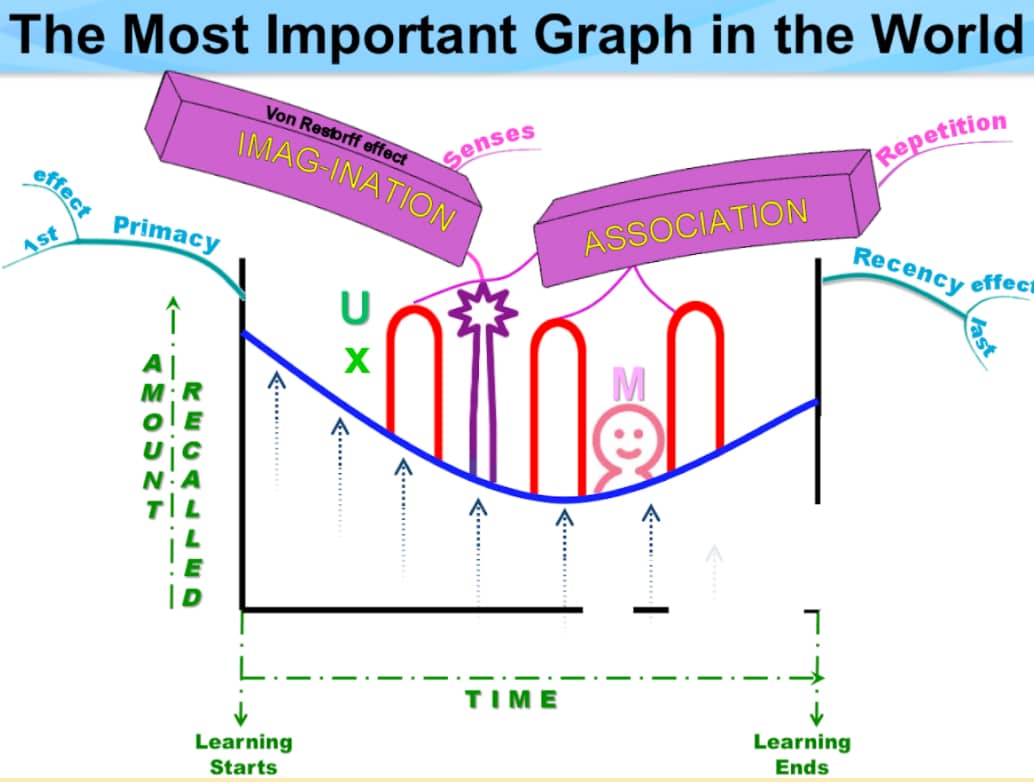

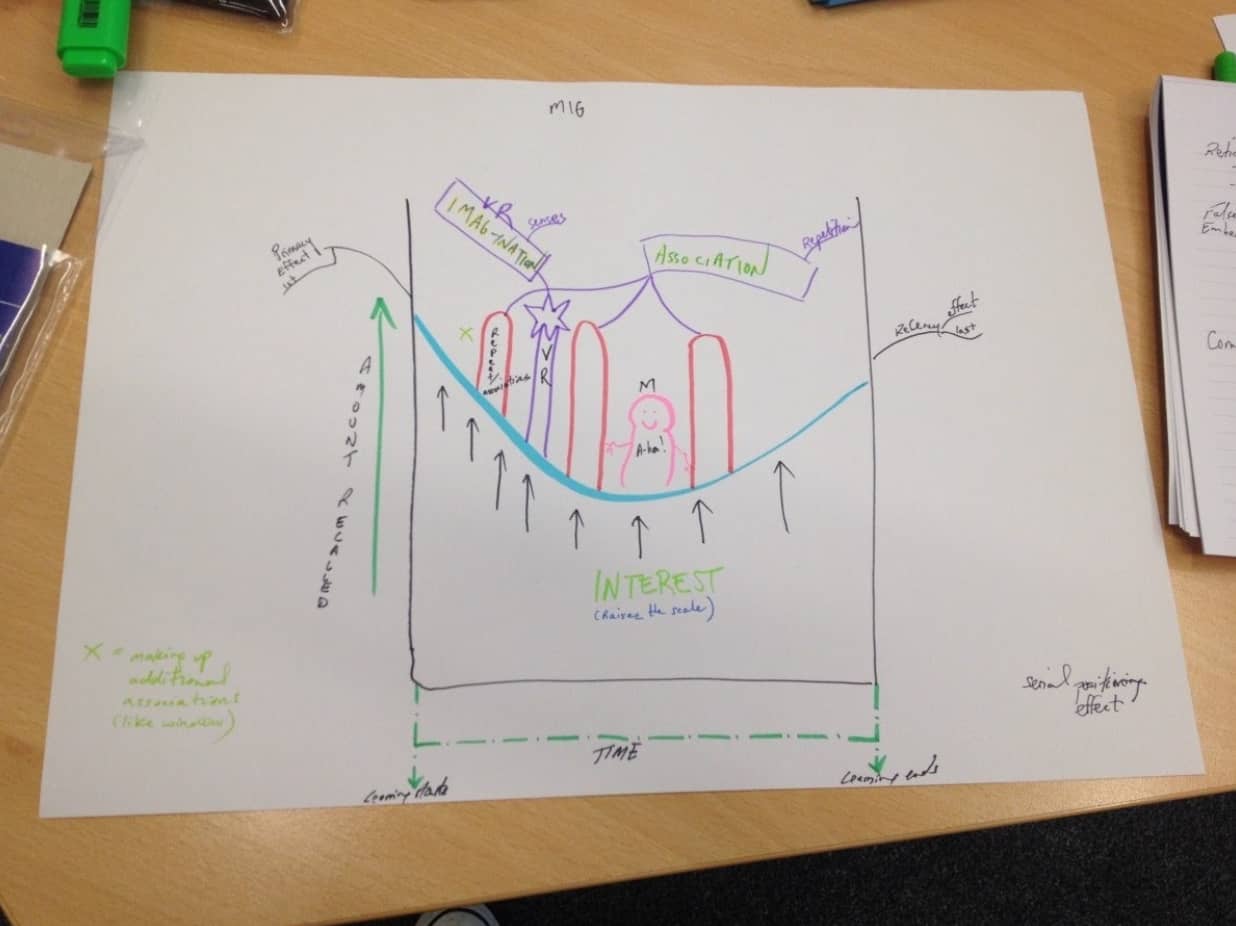

Eventually, I learned that it is worth a bit of time – and is highly engaging – to contend with graphs and charts. And the best tactic for doing so was taught to me by my mentor Tony Buzan .

As you can see, I’ve redrawn what Tony Buzan called “The Most Important Graph In The World.”

(He’s right, by the way. This graph explains the science of how to establish long term memory of information in the shortest amount of time.)

If you want a highly active means to understand visual information better, I highly recommend not only drawing graphs and charts. Discuss them verbally with yourself while drawing and later with others. When you teach, you learn the lesson twice.

The index card method I’ve shared on this page allows you to revisit only the most important information from books in a compact format.

However, sometimes you need to go back and read more. I would suggest that you turn “sometimes” into “almost always.” (Obviously, there are some books where this is not necessary. But even then, it’s worth revisiting them for better memory.)

Unfortunately, there’s no magic number for how many times you should revisit a book to keep your familiarity active. You need to decide this based on your current memory ability and your needs for the information.

But here’s a fun idea:

Place your books on your bookshelf in three categories:

Experiment with different patterns. For example, you can look through books you’ve read in the “Just read” area five times a week for the first month and then move them down one shelf.

When the book is in the “6 months” area, look at your material once monthly for six months before moving it to the yearly area. Once there, you can look once a year, or start again by putting it at the top.

This powerful variation on the Zettelkasten method helped me a lot during graduate school. Thanks to having index cards in the books, I used Roman numerals to manage the amount of reviews I’d done.

Of course, you’re probably wondering… what if I only read digital books? Audiobooks? Or what if I can only access the boo ks I read at a library?

Good questions. Here’s where using physical index cards will come in handy. You can store these and arrange them accordin g to the needed review patterns in shoe boxes.

This is how I’ve always done it. And I’m not the only one.

In fact, here’s a picture from one many Magnetic Memory Method course participants who do the same. (You can find Mike McCollum’s full success story on our community’s testimonials page .)

If you want to learn more about techniques like this, consider adding the Memory Palace technique. It’s a fun and easy process and it only takes a short amount of time to learn how:

Reading doesn’t end when you close the book. I learned this during graduate school when Dr. Katie Anderson supervised a directing reading course.

In case you’re not familiar with the term, it’s a course where you agree on a reading list with a professor. In lieu of attending a class with others, you meet with the professor and submit papers, usually for publication at the end of the course.

Dr. Anderson wanted more than just a paper from me. She wanted weekly meetings based on full book summaries I’d written.

In the beginning, the process of writing about every book and article I read for the course was a pain. But as my memory of everything I read was incredibly sharp thanks to the exercise, I soon came to love.

The best part? When you’re actively keeping those index cards and using the Magnetic Modes I shared above, writing a summary only takes a few minutes.

Of course, some people are thinking… we’re in the 21st century! Why print this summary out?

Well, when I was in grad school, I remember the very sad story of the grad student who kept everything on his computer. When his machine died, so did all of his research, including the full draft of his thesis.

He ultimately dropped out, because the pain of doing all that work over again was too much.

Sure, you can back things up in the cloud or on a backup drive, but everything digital is subject to decay and disorganization. It’s entirely up to you, but as far as I’m concerned, backing up your summaries in print is itself an active reading strategy worth putting into practice.

If you want to remember more of what you read and develop deep and lasting comprehension, these active reading strategies reap many rewards.

The more you read strategically, the more strategies you’ll discover. Each person develops their own style, relative to how consistently they practice reading.

And when you do, I hope you’ll come back to this page and share them in the comments.

In the meantime, please let me know:

Which of these strategies appeals to you the most?

Tansel Ali On How Gratitude Can Help You Remember Almost Anything 4x Australian Memory Champion Tansel Ali talks about memory improvement and the role of gratitude…

5 Mnemonic Strategies You Can Use to Remember Anything These 5 mnemonic strategies will help you use every mnemonic device with ease and efficiency.…

5 Proven Visualization Reading Strategies For Comprehension And Memory What is a visualization reading strategy and how does it affect memory and comprehension? This…